Rightfully Ours: Our Voices, Our Choices

Deb Vincent, Director of Youth Programs

Deb Vincent, Director of Youth Programs

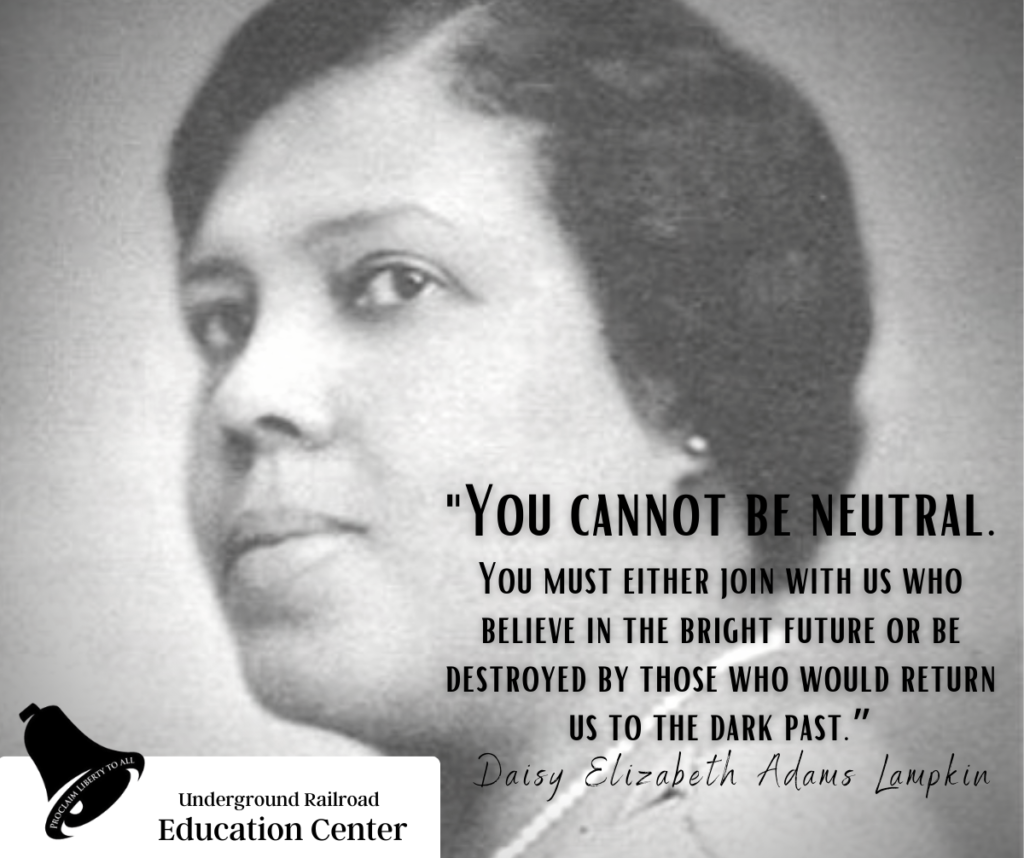

Thanks to the tireless and unrelenting efforts of women like Daisy Lampkin, our country granted the Constitutional right for equal suffrage to all citizens by ratifying the 19th amendment, finally allowing women to vote.

But then, as now, having a right is no guarantee you’ll be able to use it.

Election Day, 1920. In Ocoee, Florida, Mose Norman attempted to vote but was turned away because he did not pay his “poll tax.” a commonly used method in the days of Jim Crow used to prevent black voters from registering. A mob of white citizens followed him home, where he was dragged behind a car then hanged. The mob then burned the town and attacked the residents, eventually killing nearly every African American who lived there.

All because a black man attempted to exercise a right that was rightfully his.

By 1962, after decades of systemic practices like literacy tests and poll taxes which barred black Americans from voting and brutal, often deadly, backlash from white citizens if they tried to challenge these laws, Deputy Attorney General Burke Marshall reported that “racial denials of the right to vote” existed in eight states, with only fourteen percent of eligible black citizens registered to vote in Alabama, and just five percent in Mississippi. There were pockets with even lower numbers: eleven Southern counties with majority-black populations but no registered black voters; and a Louisiana county that hadn’t registered a single black resident since 1900.

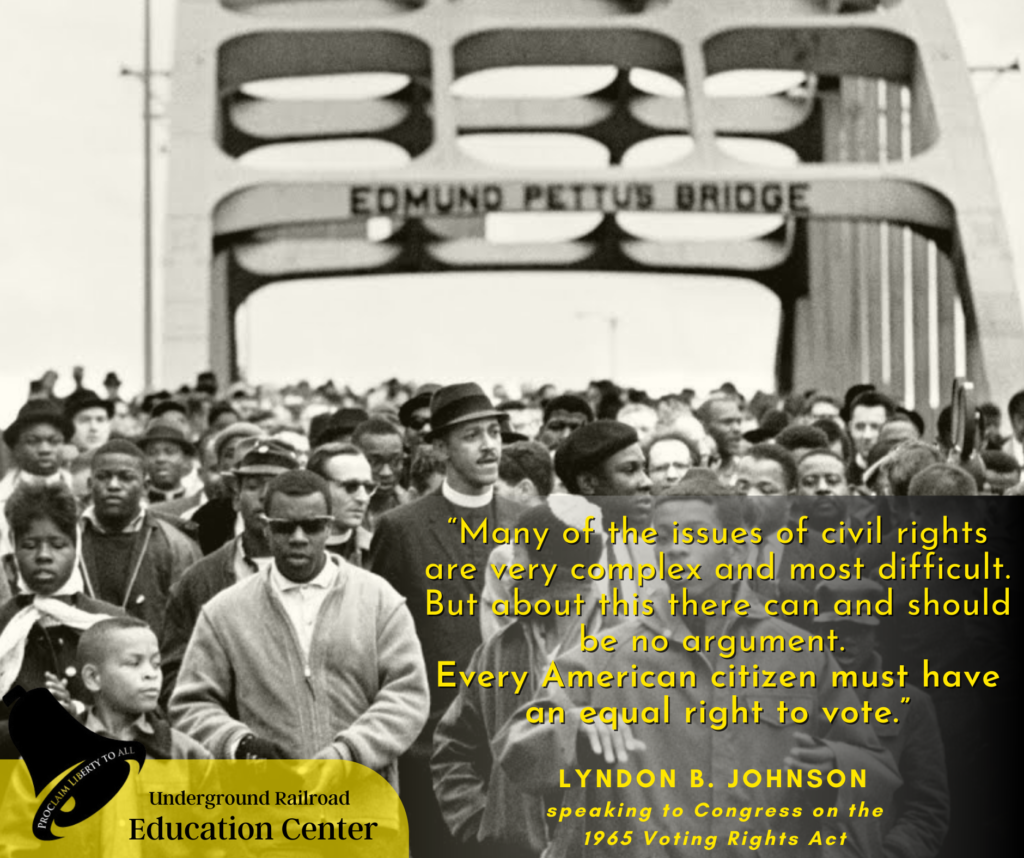

Then there was Selma and the brutal attack on the marchers known as Bloody Sunday. The march to demand access for all to the vital right of citizenship – the vote – is a pivotal event in American civil rights history, and marked the moment that the call to respect and honor the rights of all citizens to vote, regardless of color, could no longer be denied.

Then there was Selma and the brutal attack on the marchers known as Bloody Sunday. The march to demand access for all to the vital right of citizenship – the vote – is a pivotal event in American civil rights history, and marked the moment that the call to respect and honor the rights of all citizens to vote, regardless of color, could no longer be denied.

Just eight days after Bloody Sunday, Johnson addressed a joint session of Congress. “Many of the issues of civil rights are very complex and most difficult,” he said. “But about this there can and should be no argument. Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote.”

The 1965 Voter Rights Act would soon follow.

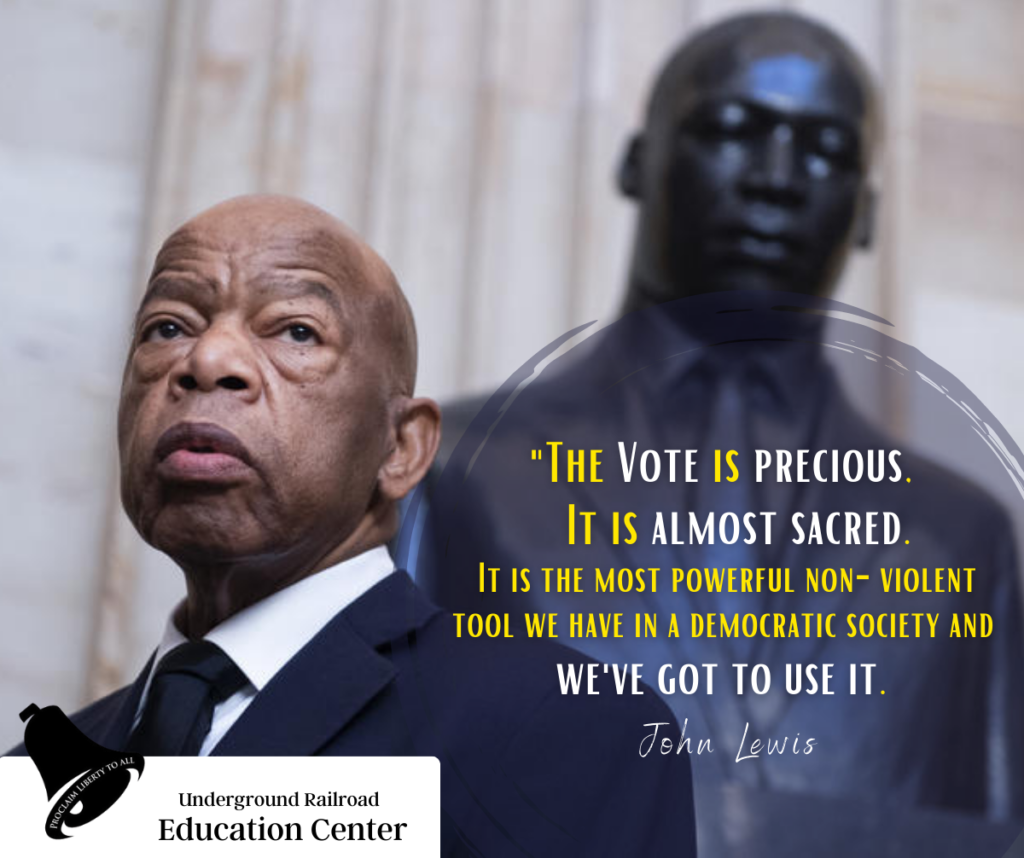

Despite the protections of that landmark legislation, attempts to disenfranchise large swaths of voters continue. “Voter discrimination is on the rise,” said John Lewis in August 2018. “Thousands of people of color are being systematically denied access to the ballot box, many of whom have voted all their lives.”

Today, as we are faced with a bitterly contentious race, the literal and publicly acknowledged attack on our right to vote and be counted continues. Black voters are being systemically removed from voter records, polling places are being closed in predominantly black neighborhoods, the value of absentee ballots is being questioned and voters are being intimidated into not voting in many states and cities.

Today, as we are faced with a bitterly contentious race, the literal and publicly acknowledged attack on our right to vote and be counted continues. Black voters are being systemically removed from voter records, polling places are being closed in predominantly black neighborhoods, the value of absentee ballots is being questioned and voters are being intimidated into not voting in many states and cities.

In North Carolina, with a close election for control of the state legislature, 40% of rejected mail in ballots were from black voters, (theguardian.com). In Greensboro, a group of men, women and children peacefully marching to early vote were pepper sprayed by police on their way to the polls. 12 were arrested. Over 200 voters were blocked from voting.(cnn.com).

Our vote matters. We cannot be neutral in this, and we cannot accept that our vote is valueless when so many have shed blood to secure it. To choose not to vote is to say their sacrifice was worthless, and gives our future over to fate.

“Ours is not the struggle of one day, one week, or one year. Ours is not the struggle of one judicial appointment or presidential term. Ours is the struggle of a lifetime, or maybe even many lifetimes, and each one of us in every generation must do our part.”

John Lewis

Protecting and keeping the precious right of others to vote, safely and without interference, has always been part of the abolitionists charge.