The More Things Change, The More They Stay the Same

In our increasingly polarized society, the symbol of the 19th century Underground Railroad movement and its abolition activists challenge us to publicly reflect and act upon the legacy of the institution of slavery in our contemporary times.

(P. Stewart)

Who are we?

Underground Railroad Education Center researches and preserves the local and national history of the Underground Railroad movement as the first civil rights movement, its international connections, and its legacy within the ongoing struggle for equity, freedom, and justice, thereby empowering people of all ages to be agents of change toward an equitable and just society.

As a historical and educational organization, we endeavor to place the current issues we face nationally and here in Albany within a historical framework for understanding. Why is this of importance to us? Black abolitionists not only strategized on how to abolish the institution of slavery and how to meet the needs of freedom seekers, but they also strategized on how to respond to issues of equity in housing, voting rights, healthcare, jobs, education, issues that continue to plague us today. We follow in their footsteps.

It is profoundly important to remember that the mission and activities of the Underground Railroad Movement were illegal under the laws of the day.

Believing those laws were unjust, both Black and White abolitionists actively worked to change those laws while they willingly, knowingly, and actively broke those laws to ensure the freedom of the formerly enslaved people they served.

The historical record tells us that broad inequities in policing and the justice system have existed and continue to exist in the Capital Region of New York State, the nation, as well as here in Albany.

Language has Power.

Whose voice do we recognize in the language we use to speak about and remember this important aspect of the American narrative?

Language underscores and perpetuates inequities, and language perpetuates and underscores equity and justice. Language has the power to color the beliefs and influence the actions of those who use it and hear it cannot be underestimated. Within The Vocabulary of Freedom, even the historical language of describing an enslaved person seeking freedom as a “fugitive” is deeply problematic. The word “fugitive” reinforces the stereotype of Black criminality and takes autonomy away from the enslaved person, without acknowledging the agency of the individual and the immorality of the legal structure that supported enslavement. Additionally, it completely ignores the bravery of the enslaved individual who, in choosing to seek freedom, risked everything. Replacing fugitive with Freedom Seeker or Self-Emancipated is an effort to use language to dismantle racism.

We believe that language matters, holds the weight of action, and is often defined by the group in power. The use of the term “riot” is itself arbitrary, and the application of this term to authorize the use of force (including tear gas and projectiles) has historically proven to disproportionally increase the risk of harm to innocent people.

We believe both our nation and the City of Albany have a long history of mistreatment and undue harm to members of the black community by members of law enforcement. We welcome the verdict in the Chauvin case as appropriate justice and a step forward, and we recognize that much remains to be done to correct a system that has traditionally done harm to members of the black community. History and statistics suggest that increased funding, increased policing and “community policing” models have not led to safer communities for people of color.

It is time for the system to change.

We believe language that links protests and acts of civil disobedience to dangerous attacks on our country cause harm to POC and those who support them and create barriers to the healing and empowerment of our community and puts vulnerable people at risk of harm.

Riot or Rescue?

The Federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 requires that all self-emancipated enslaved persons be returned to their former enslavers in the south. The effort to “recover property” was a lucrative business, employing a large number of bounty hunters and providing offers of large rewards for information leading to the return of these individuals. Law enforcement and other government officials in the north, either complicit (or compliant) in these laws, used the full weight of law enforcement to capture and return formerly enslaved people to their “rightful owners.” Further, every citizen was legally required to assist them in their efforts, and refusal to do so was a felony federal offense. As such, the risk of capture was quite high even in Albany, and rescues were a regular occurrence. While predominantly non-violent, abolitionists could be found engaging in physical conflicts so as to prevent what they saw as the kidnapping of innocent people.

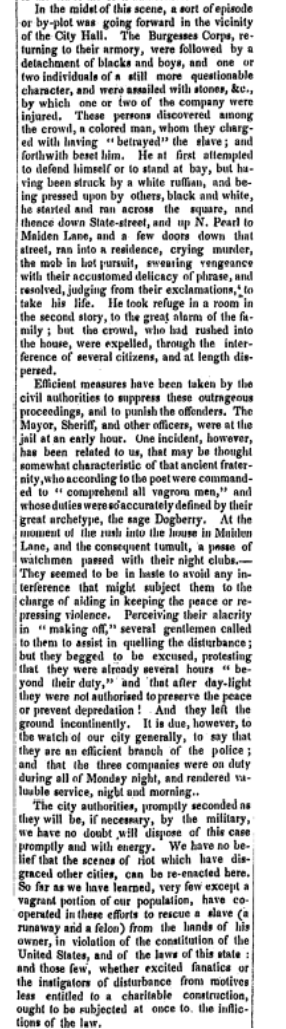

On many such occasions, large groups of abolitionists and other free Blacks often gathered to rescue the captured individual. This was invariably deemed “a riot” by the press, who claimed these acts were an affront to law and order. Although there are no reported injuries to the rescuers in these incidents (at least here in Albany), they were certainly met with force from armed officers, often assisted by military and members of the night watchmen.

The language used in the day is also chilling and eerily familiar. Headlines ranged from “Riot in Albany” to “Fruits of Abolitionists,” and “Abolitionist Mob.” Self-emancipated persons, guilty of nothing more than seeking freedom from bondage, were runaways, felons, and fugitives. Rescuers were vagrants, mobs, “excited fanatics”, and “instigators of disturbance” whose motives were “less entitled to charitable construction.” An article describing the rescue of Charles Nalle describes a crowd “threatening” a rescue, who were said to have knocked down the Sheriff, then seized the “captive” and “formed a single file, much like that of convicts in their march to their meals in the State Prison.” “Blows, knock-downs and pistol shots were occasioned,” and “colored persons were the most active participants in the melee.”

Justice was on the side of the oppressor, opposition was an attack to the “supremacy” of often unjust laws, and all who protested these injustices were participating in “mob-law.”

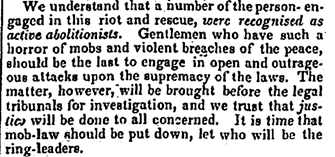

Case of a Slave

Albany Argus, July 25, 1835

Good Trouble or Inciting Trouble?

The Civil Rights Era of the 1950’s, ’60’s, and ’70’s created great changes across the nation and here in Albany. Frustrated with the continued politicization of policing in Albany and witnessing multiple acts of police brutality as well as lack of equity in services and job availability, a group of concerned African American men formed The Brothers. Created in 1966, 6 months prior to the formation of the Black Panthers, these men believed in community action, protest, and “creative trouble” (they once piled garbage on the steps of City Hall to force the mayor to institute free municipal garbage pickup.)

Their methods worked.

Militant but non-violent in action, they began publishing a paper they named The Liberator, highlighting the inequities in Albany and calling out police misconduct by name. They actively and nonviolently protested and picketed City Hall and were arrested “too many times to count” in response to their action.

The Brothers recognized that the APD was deeply embedded within the machine-controlled criminal justice system, which elected its judges, its county attorneys, and (until 1968) its DA, with the blessing of the Democratic Committee. The Brothers successfully worked to dismantle the political machine, including working to end the wide-spread practice of purchasing votes to buy an election.

The city had recently dealt with the case of Samuel Clark whose alleged beating in 1962 at the hands of the APD after double-parking resulted in an argument with an officer resulting in a major investigative article in the Knickerbocker News and protests led by the NAACP. Unfortunately, while it raised awareness of the problems, no changes were made in the APD, nor were White officers held accountable, despite witness accounts.

The Liberator also published multiple accounts of police brutality witnessed both here in Albany and nationally, including the beating and arrest of an unarmed, non-violent Black woman outside her Clinton Avenue home where she was seen being forcibly hauled away, leaving her unattended child behind.

When The Brothers showed no signs of slowing down their cause, “the local and state police department took initiative to control the group by tapping headquarters’ phones, taking photo surveillance, and unlawfully placing some Brothers under arrest on inflated charges. Both Mayor Corning and the police department kept routine tabs on the most active members who posed the largest threat to corruption, and searched for ways to silence the organization.” (The Northern Civil Rights Movement: How The Brothers Fought Housing, Employment, and Education Discrimination and Police Brutality in Albany, NY, Paige McGinnis)

The Albany police force was an extension of the Corning political machine and used police brutality to exercise control over Blacks, keeping them subordinate and underfunding their neighborhoods in favor of other city projects. As communities became more aware and increasingly frustrated by this treatment, tensions began to rise, particularly among the youth in Albany. The Brothers actively worked to calm these tensions and prevent violent interactions between Black community members and the PD.

After a patrol car nearly backed into a young Black mother carrying her child, an argument broke out between the officer and the woman. The Brothers arrived at the scene and observed growing tensions between teenagers and officers. The Brothers viewed the teenagers’ feelings for Whites as “pure hatred,” yet they were able to separate the crowd from the police by forming a human chain and driving the young people down the street. They convinced 40 to 50 of the angry youths to attend an immediate meeting at The Brothers office around four blocks away.

The police were prepared to start shooting at the time.

When The Brothers met with the Police Chief to share their concerns about the teens – that the teens were tired of oppression and tensions were on the verge of erupting – The Brothers warned the Albany machine that they might not be able to hold the teens back if Albany failed to make improvements. The Chief denied that policemen had struck teenagers with their clubs and that they had their guns drawn. Instead, several members of The Brothers were charged with inciting a riot, arrested, and convicted.

Despite all, The Brothers was peaceful and did not promote violence. Rather, they believed in legislative action to combat systemic racism. “We must elect Black leaders. We must demand improvements in the city’s care of our section of town. We must demand control of the schools our children attend. We must demand the justice this country has always promised, but never delivered.” The Brothers encouraged Blacks to keep their composure under frustrating circumstances, especially when dealing with police, believing every vice in this city operates with the consent and complete knowledge of the police department. One of the outcomes of The Brothers political concerns was the election of Nebraska Brace as the first Black to serve on the City council. While pro-machine candidates tried to maintain the Arbor Hill area’s representation, Brace’s success grew out of his grass roots connections and work with Arbor Hill based Black masonic lodges. Policing was one of the issues of highest concern.

Want to learn more about The Brothers? Watch the short documentary film, The Brothers: The Forgotten Struggle For Civil Rights in Albany on PBS

The Era of Community Policing

The demise of the political machine in the 1980s brought an era of great change to the APD. The City made efforts to bring on Black police officers. One of the Black officers who successfully rose through the ranks to the role of detective was John Dale and in 1989 Dale was appointed chief of Police by Mayor Whalen. As Jerry Jennings entered the Mayor’s Office in 1994, the APD was charged with recreating itself under a Community Policing model. Departments were rearranged and training ensued. Dale retired in 1995. The plan particularly encouraged foot patrol officers to access other city agencies for help in dealing with community concerns ranging from criminality to parking violations and including such things as vacant buildings in need of stabilization, pavement in disrepair, speeding on neighborhood streets, debris strewn lots, abandoned cars, elderly persons in need of assistance, etc, calling for the department to authorize them to make the necessary contacts.

However, the model proved to have several underlying challenges. One was a lack of funding for adequate personnel and ongoing training. Another challenge was the lack of understanding and application of the concept of intersectionality to this situation. It also served to dramatically increase arrests for small crimes and infractions that had previously been “allowed to slide.” Under the new program, arrests were made for loud music, parking violations, and other “quality of life” crimes that often placed Black and brown individuals into the system with a record that could later be referenced in court, putting low-income people at greater risk of incarceration due to a lack of bail money. Police began to believe that enforcing misdemeanor laws had a direct relationship to the control of serious crime, for offenders stopped on minor violations often turn out to have signs of serious criminality like drugs, concealed weapons, outstanding warrants. This was the widely accepted “broken window” theory that community safety was enhanced by addressing these lesser issues. Even with its challenges, Community Policing contributed to a positive shift in police-community relations. While not perfect a as implemented, Community Policing contributed to a dramatic improvement over previous practices.

Biased or Balanced?

Under Mayor Whalen’s watch, police misconduct and reports of entrenched racial bias in policing led directly to a 1989 secret investigation monitoring activity at the Albany Greyhound Station. The report noted that, “not a single White person was stopped, or questioned, and not one Black or Latino had gotten through the bus station without being stopped.”

The NYCLU also called for an investigation after three young Black men were arrested by police during a street disorder outside the Albany Domino Club. The men claimed police hurled racial slurs, beat them, and unleashed a police dog on them outside the club. After community members held several protest marches, the Police Department began an internal investigation into the actions taken during the incident. Under the leadership of Mayor Jerry Jennings, another young African American college basketball star, Jermaine Henderson, was arrested after an alleged altercation with two White off-duty police officers, William Bonnanni and Sean McKenna, in an Albany bar. Henderson, while handcuffed, was allegedly beaten by the two White officers in the police station garage.

The officers were disciplined by the department. In the case of Henderson, the officers were suspended for 30 days without pay and assault charges were filed against them. This led to protests by police officers and the Albany Police Officers Union, who were extremely critical of the departmental disciplinary actions. (http://www.cflj.org/cflj/The-Last-Half-Century-of-Systemic-Racism-in-Albany.pdf)

In 2009 an interesting turn of events took place that ushered in a new chapter as Albany’s Police Department struggled with its internal challenges. Police Chief James Tuffy, a self-styled “tough guy” appointed by Mayor Jennings to lead the Department was overheard using a racial slur toward black community members. He tried to deny he had said something derogatory. He turned to his subcommanders to back him up but they all refused. In the subsequent turmoil one of the commanders, Steve Krokoff, became in 2010, the Chief. Krokoff and the next two chiefs that followed him (Cox and Sears) instituted and sustained an effort at Community Policing highlighted by the formation of the Albany Community Policing Advisory Council. The council consisted of a wide range of community leaders and neighborhood activists and police officers and was initially embraced by the community. As the meetings continued and the committee’s focus became unclear it lost influence. Notably Steve Krokoff was the first Police Chief that held an advanced degree. His administration and to a large extent those who followed were noted for their openness and connectedness to the community. Following Sears, the present chief, Eric Hawkins, an African American, was appointed by Mayor Sheehan, the first woman Mayor of the City of the City of Albany

Today, Albany is still challenged with issues of alleged police misconduct. It is the subject of at least one pending police misconduct lawsuit related to the shooting of Ellazer Williams in 2018. Additionally, the Albany D.A. charged a police officer with felony assault and official misconduct related to a confrontation between White APD officers who were called to a loud party, where the officers are seen in body cam video beating three Black First St. residents. Two of the men who were beaten by APD officers have since won settlements in their federal lawsuits against the department. It should be noted that the officer charged with the felony was fired and then reinstated by an arbitrator. Mayor Sheehan has publicly called this decision a racist decision.

There are other recent claims made against the Albany PD, including allegations of racially motivated misconduct and use of excess force related to Black Lives Matter protests (identified by police as riots) that have taken place since May 2020. There are numerous complaints and video of police use of force against protestors and bystanders, including alleged assaults resulting in injury to the protestors, and the use of pepper spray/tear gas and other non-lethal force on groups of protestors which included minors.

In fact, tear gas has been used only twice in the history of the City, both times in response to Black Lives Matter protests in May and June 2020 where some participants became violent toward police. Further, the Mayor has made public statements justifying the need for its continued use by comparing protestors to those who attacked the Capitol on January 6. While the comparison is flawed, the concern of protestors over-running a facility had validity because of incidents in Seattle, Minneapolis and Portland in 2020 where protestors took control of police related facilities.

Of note, the Albany Police Department was named in President Obama’s 2016 Task Force on 21st Century Policing as an example of what to do right. Furthermore, Albany police supported two days of peaceful protests in May and June of 2020 and again in April 2021 during the 90-minute walk by BLM protestors to the South Street Station.

In spite of these facts, and all of the work done over the previous 3 decades to reform policing, challenges persist. Officer David Haupt of the Albany PD was caught on body cam making racially charged statements. He has since been terminated. As shared by Officer Anderson in a November 2020 interview on WAMC, he believes Albany has been a frontrunner in fair policing for decades. Anderson also explains the increase in violent crime in Albany in 2020, asserting, “Bail reform. Discovery reform. The

George Floyd incident, and the pandemic – all at once – within a short period of time – has changed policing.”

But the community still bears scars of past and recent history. “We have a long history of police brutality in Albany and of killing of Black people,” says Dr. Alice Green of the Center for Law and Justice (ACLJ.org) “No, the country didn’t hear about Ellazar, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. After the APD cleared Detective James Olsen of any wrongdoing, Green says the community hasn’t trusted city police since.”

We Believe

Policing’s embedded institutional racism and its roots in the institution of enslavement centuries ago still matters because policing culture has not changed as much as it needs to, here in Albany and across the nation. For many African Americans, law enforcement represents a legacy of continually enforced inequality in the justice system and its resistance to advancement – even under pressure from the civil rights movement and its legacy – which engenders deep frustration and mistrust among members of the community. However, it must be remembered that in Albany Ken Wilcox, John Dale, Kelly Kimbrough and even Eric Hawkins represent a thread within the Black community that says, “We need to be represented in this institution and our presence here helps make things better”. Many see it as a path for advancement and getting real justice for the community. The election of David Sores as DA is also relevant. The election of a black DA changed the landscape.

While we leave you to read the record so you may understand the past and be empowered to act in the present, we assert the following in support of our community:

- Language matters. It informs action and is often defined by the group in power. Collectively we need to use antiracist language and actions to dismantle systemic racism and promote healing and empowerment in our community.

- We welcome the verdict in the Chauvin case as appropriate justice and a signal that we may be stepping forward. We recognize that much remains to be done to correct a system that has traditionally done harm to members of the Black While we do not know what the answer is, we do know that history and statistics suggest that increased funding, increased policing and “community policing” models are a beginning, but they need to be coupled with a sustained commitment to antiracism.

It is past time for the system to change

We need to be aware of and actively practice antiracist behavior and ways of thinking, “Because your opponent isn’t a person, it’s the system of racism that often shows up in the words and actions of other people.” (So You Want To Talk About Race, Ijeoma Olua, p.48)

References:

Fruits Of Abolitionism, Tue, Jan 17, 1837, Albany Argus (Albany, NY)

Case of a Slave, Sat, Jul 25, 1835 | Albany Argus (Albany, NY)

Double Parking While Black, Posted by 98 ACRES IN ALBANY on JANUARY 3, 2019

The Brothers Series, Albany Times Union

Round table discussion on race, By Michael Rivest on May 6, 2016 at 12:41 PM

The Brothers and the Future By Michael Rivest, April 6, 2016

The Northern Civil Rights Movement: How The Brothers Fought Housing, Employment, and Education Discrimination and Police Brutality in Albany, NY, Paige McGinnis

Policing, Racism And The Black Lives Matter Movement In Albany, By Jackie Orchard, Nov 27, 2020, WAMC.org

How Police Unions Fight Reform, William Finnegan, July 27, 2020, The New Yorker.

Excessive Force, Brutality, and Unlawful Shootings by the Police in New York State, joneshacker.com

Protests in the Capital Region calling for Albany police officers to be fired and justice by WRGB Staff Saturday, April 17th, 2021

So You Want to Talk about Race, Ijeoma Olua, Seal Press, 2018

Video alleges police brutality in Albany, by Peter Eliopoulos, Sep 3, 2019, News10.com

South Station Protestors In Albany “Here To Stay” By Dave Lucas, Apr 19, 2021, Wamc.org