John W. Jones and the Underground Railroad in Elmira, NY

From The Freedom Seeker Vol 13, Issue 2, Summer/Autumn 2016

By Deborah A. Lee, Independent Scholar

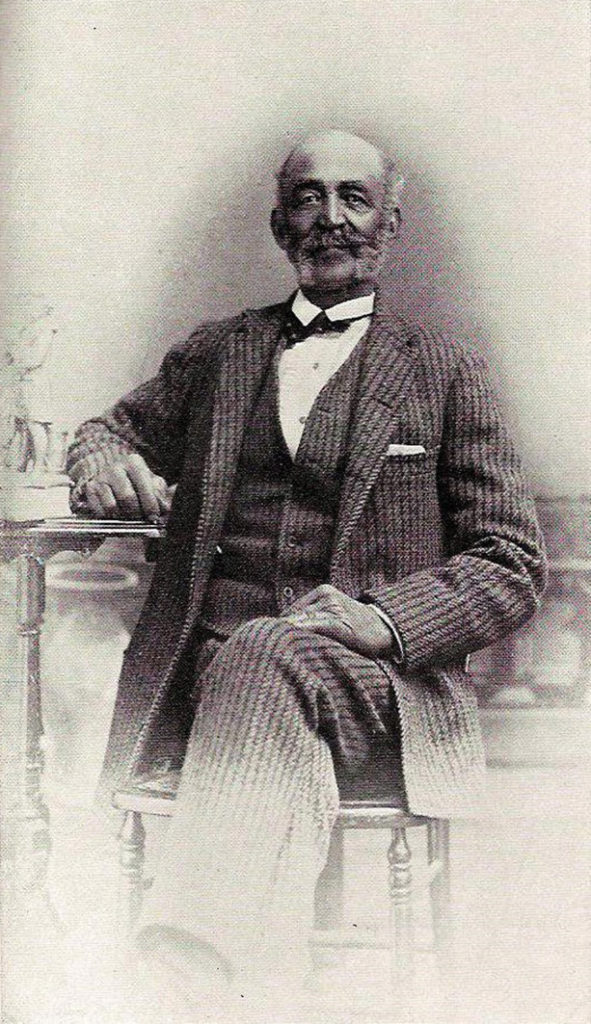

The Underground Railroad network, by its nature, attracted humanitarians of character and integrity. One little-known man who shone among them is John W. Jones, who escaped from slavery near Leesburg, Virginia, and helped more than 800 people to freedom through Elmira, New York. Because of his character, biography, and longevity, an unusual wealth of local sources document the secret network.

The Underground Railroad network, by its nature, attracted humanitarians of character and integrity. One little-known man who shone among them is John W. Jones, who escaped from slavery near Leesburg, Virginia, and helped more than 800 people to freedom through Elmira, New York. Because of his character, biography, and longevity, an unusual wealth of local sources document the secret network.

Jones’s life reveals strategy and tactics of the underground railroad in the Mid- Atlantic region and the high level of communication and organization across race, class, and other boundaries. In Virginia, Jones enjoyed close relationships with his grandmother, mother and siblings and with the overseer, his wife and children. Jones waited until 1844, when slaveholder Sarah Ellzey was near death and his youngest brother George was eighteen before fulfilling his own and their mother’s dream of escaping to the North with his two brothers. He recounted his harrowing journey later in life. His first taste of real freedom came during a meal shared with underground railroad agents Nathaniel and Sarah Smith on Independence Day. Thanks to the welcome from such activists and the abundance of jobs in the prospering region, Jones and his four

companions settled in Elmira, where he learned to read and write, found work, and joined the network to freedom.

John W. and George Jones (assumed names) collaborated with black and white antislavery activists such as Rev. Thomas K. Beecher, financiers including Jervis Langdon (later Mark Twain’s father-in-law), and William Still in Philadelphia, to run a highly organized operation. Jones placed freedom seekers on the 4:00 a.m. train to St. Catherine’s, Canada. There, a church committee welcomed them and helped them get settled. In 1850, Jones served as a marshall in a large regional celebration commemorating freedom in the West Indies, with a parade and prominent black abolitionist speakers. In 1854, after a high-profile capture of freedom seekers in New York City, the Vigilance Committee in Philadelphia used the Elmira route whenever possible. Jones never lost a passenger.

Jones communicated with family and friends in Virginia and helped others join him. A sister and a niece lived with Jones and his wife in 1855. In 1863, after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, another sister and her grown children moved there. Communications were easy, he told a reporter; letters were sent to southerners via friends in Canada. During the Civil War, Jones respectfully buried the Confederate dead from the Federal Prison Camp in Elmira, and contacted his overseer when he recognized the man’s son among them. After the war, Jones visited the Ellzey farm and was welcomed as a guest.

In 1896, Susan Langdon Crane interviewed Jones for Ohio State University professor Wilbur Siebert. Jones admitted—but only after his compatriot died—there was a black man who forged freedom passes, and Elmira activists communicated with Quakers in Pennsylvania and Maryland, using horses as code. Crane told Siebert she did not understand, but likely the code was used for color and height and then the forged freedom papers were sent south, where they would be needed.

In all he did, his interviewer wrote, “Jones felt that it was his duty to put the golden rule into practice.” Another citizen wrote, “No resident of Elmira, white or colored, ever commanded greater respect and admiration.” After John W. Jones’s death in 1900, locals learned that he was the one who secretly placed flowers weekly on Sarah Smith’s grave—he never forgot her kindness during his freedom flight. Nor should we forget his, along with his effectiveness in the underground railroad network and the documentation he left behind.